Recharging Yourself As A Leader—3 Laws Of Managing Energy

Recharging Yourself As A Leader—3 Laws Of Managing Energy

by Ginny Whitelaw. Originally published on Forbes.com

Look up any list of the top challenges currently facing leaders—Forbes, McKinsey, Gallup, KornFerry, each have their list—and, despite some differences, they all rest on a common denominator: They all require an enormous amount of energy and learning agility from leaders, not only for personal stamina, but for engaging and inspiring others. These can be tiring, disorienting times, with rapid competitive pivots, new ways of working that aren’t always working, mass resignations, and increased strains on mental and physical health. How can we find the abundant energy needed to be bigger than the challenges we face and be a guiding force for others? Here are three laws of energy management that, on the one hand, can guide us and, on the other hand, we break at our peril.

Law #1: Rhythm, Not Relentless

In The Power of Full Engagement, Loehr and Schwartz highlight that managing energy is key to peak performance, and that rhythmic, daily rituals to stretch and renew are key to managing energy. From their work with peak-performing tennis players, for example, they found that those who remained energized up through the last games of the last set had developed mini-rituals for renewal even in the brief moments between games, shaking out their limbs or joshing with the crowd. We know from studies of the nervous system that when it’s exposed to the relentless push, push, push of stimulation, it habituates, becoming less responsive over time. To maintain peak performance, we have to change up the pattern of what we’re doing—not so often as to continually distract ourselves (which extracts its own price in performance)—but with purposeful breaks and rituals that keep us fresh.

While good diet and sleep habits are important to a healthy, daily rhythm, there’s more to it than that. The rhythm we want to establish is between challenge and renewal, between stretching ourselves into facing perhaps one of those top challenges, and then recharging. A best practice for this rhythm is about 90-minutes of challenge time, followed by at least a few minutes of a renewing break and, at least once a day, 30 minutes or more of state-changing physical activity. For leaders whose work is mostly sedentary, those few-minute breaks can be a welcome relief to step away from the computer, get outdoors, and do some deep breathing, light stretching or shake out sleepy limbs. The 30-minute breaks might be time for a workout, a walk in nature or playing a musical instrument. The point of these daily rituals is to interrupt the cycle of busy, that is, of work feeling like a relentless (and often speeding-up) treadmill. Instead, we can find a regenerative rhythm so that we keep cycling back to a full charge.

How we find that rhythm in our own workday is not only important for our energy but serves as a model for others. They, too, need their best energy to stretch themselves into the challenges they’re facing. As employee engagement and wellness sit on many of those lists of top leadership issues, modeling how to have energy for the game is a good way to promote both.

Law #2: Down, Not Up

Hot-headed, upset, uptight, spun up: common terms in our language pretty-well describe what happens when tension and unruly emotions fill our body and mind. Energy rises up and we become less strong and stable. Elite athletes and martial artists know this phenomenon well, which is why the best of them have centering rituals for bringing the energy back down into their feet or lower abdomen, and not getting riled up in their heads. In Aikido, for example, two of its basic principles are to keep centered in the hara (i.e., lower abdomen) and feel weightedness from underneath. When someone moves from this condition, they have the power and stability of a tank. Conversely, when they’re up in their shoulders or head they’re as unstable and easy to push over as a person standing tip-toe on a pole.

While most of us don’t face physical pushing in our day-to-day work, physical and psychological stressors land in us in similar ways, triggering increases in catecholamines, blood pressure, heart rate and muscular tension. Our resourcefulness in handling stressors comes from this inner way of managing our energy down, calming down, settling down, as opposed to letting them “up”-set us.

In leadership, this condition is further evident as part of leadership presence. It communicates to those around us whether “we’ve got this” or we’re barely hanging on. We as humans keenly sense this in one another because, at a level deeper than we may even be conscious of, we’re deciding whom we can trust enough to follow.

A best practice for managing one’s energy down, not up, which also makes for a refreshing few-minute break, is hara breathing.

- 1. Grounding: Stand comfortably, feet shoulder width, knees soft, feet soft on the ground. Let your eyes soften, that you can see all around you (180-degree vision) and nothing in particular. Press your hands together and press your big toes into the earth, noticing a “thereness” or alertness at the base of the hara. Release the pressing and notice it goes away. Try this a few times using only your toes to get the feel for how extending the toes into the earth “wakes up” the hara.

- 2. Inhale: Allow a relaxed inhale to fill your body as if from the ground, expanding the hara, floating your hands, palms up, to the level of the solar plexus. Keep shoulders relaxed (See Figure 1).

The inhale and exhale of hara breathing. FROM RESONATE, DRAWING BY MARY MICHAUD

- 3. Exhale: As exhale begins, set the hara by slightly pressing your big toes into the ground, turn your palms downward and gently push them down. Let your exhale slowly drain down through your hara, through your big toes, into the earth.

Repeat 3 times, letting each exhale get progressively slower.

Law #3: Out, Not In

Once we have energy to work with and we know how to remain centered, how do we use energy in ways that move us toward our goals and help others move with us?

We can again look to Aikido for a principle that is as true in leadership as it is in the physical moves of a martial art, and that is to extend energy toward where we want to go. Inasmuch as we want others to follow, we pick a direction that they can follow, too.

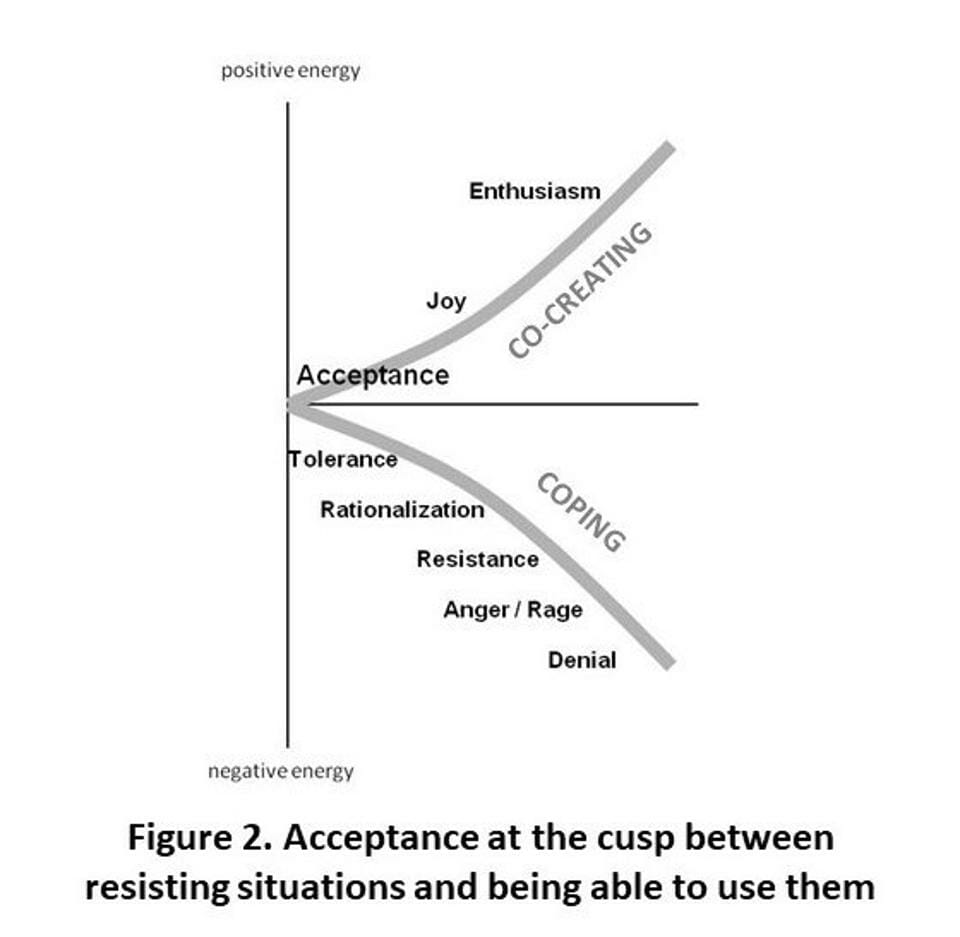

This may seem simple enough, but it represents a potentially profound “flip,” in the body and mind of a leader from subtly resisting life to accepting and working with it. This is the first flip of Zen leadership—from coping to co-creating—because without this flip, we’re not even leading. We’re not going anywhere productive; we’re stuck. In coping mode, strong or subtle resistance locks our focus on problems and people we don’t like or are simply tolerating. In co-creating mode, our energy is free to flow toward things we do want, people we do serve, with a sense of opportunity and purpose. At the cusp between coping and co-creating is the critical neutrality we call acceptance (See Figure 2).

Acceptance doesn’t mean we necessarily like what’s going on; it means we accept it is what it is and figure out how to work with it. If you were to physically model what acceptance feels like in your body, you’d probably notice your shoulders dropping, your body relaxing just a bit. And so it is that our own relaxation is key to being able to extend energy out toward what we want. It’s also key to being able to sense others and how they might move with us. Just as a calm pond more clearly reflects the sky and shoreline, so a calm mind more clearly reflects the people and conditions in its midst. Co-creating and realizing outcomes consonant with our purposes and goals generates joy, even enthusiasm, as energy builds. Hence Eckhart Tolle’s wise observation, “If you’re doing anything not in the state of acceptance, joy or enthusiasm, just stop.” Actions from coping mode generally muck things up further.

Acceptance at CuspFROM THE ZEN LEADER, DRAWING BY GINNY WHITELAW

Which leads us to the inter-relatedness of these laws and the peril of breaking them. It’s easy to fall into in coping mode when we’ve lost our center or we’re physically exhausted. In fact, catching ourselves in the act of coping can become exactly the signal we use to stop. We do well to recharge, renew or give ourselves time to heal to the point of acceptance in order for our presence and actions to again become a positive force. If we can use the warning sign of coping mode well, we will drop out of relentless activity to recharge, center ourselves in hara and, once again, be able to extend our energy toward the purposes that call us, the people we serve and future we want to create.

Ginny Whitelaw is the Founder and CEO of the Institute for Zen Leadership.

Do we know how to find you?

If you received this from a friend and want your own monthly boost of insight and resources, let us know.

Published on Oct 07 2022

Last Updated on Feb 01 2024

By emilya